The story of physical movement as a form of structured exercise is as old as civilization itself, yet its evolution reveals a fascinating tapestry of cultural values, scientific understanding, and shifting human aspirations. It is a journey that begins not in a mirrored room filled with chrome equipment, but in the dusty arenas of ancient Greece, where the cult of the body was inextricably linked to ideals of virtue, beauty, and military prowess.

For the ancient Greeks, physical training was a civic and moral duty. The gymnasium was not merely a place for exercise; it was a central institution for education and social life. Here, young men trained in the palestra for wrestling, a discipline that required immense strength, agility, and technique. They practiced running, discus, and javelin, events that would become the foundation of the Olympic Games. The ideal was arete—a concept of excellence and the fulfillment of purpose. A well-trained body was the visible manifestation of a disciplined mind and spirit, epitomized by the perfectly proportioned marble statues of athletes that have endured for millennia. This was the original "classical" physique, born from functional, compound movements performed with nothing more than one's own body weight, simple stones, and friendly competition.

The Roman Empire, ever practical, adopted and adapted the Greek model to serve its vast military machine. For the legions of Rome, physical conditioning was a matter of life, death, and imperial expansion. Their training was brutally functional: marching for miles in full kit, digging fortifications, and practicing with heavy wooden weapons. Strength and endurance were paramount, cultivated through exercises that mimicked the demands of warfare. While the Greek ideal of aesthetic balance persisted, the Roman emphasis was overwhelmingly on utilitarian strength and collective discipline, a shift that moved physical culture slightly away from art and closer to the science of survival.

With the decline of Rome and the rise of Christianity in Europe, the classical view of the body as a temple gave way to a perspective that saw it as a vessel of sin. For centuries, formal physical training was largely abandoned, preserved only in the martial traditions of knights and the folk games of common people. The Renaissance, however, sparked a reawakening. Scholars rediscovered Greek and Roman texts, and with them, the classical ideals of harmony between mind and body. This period saw the publication of early treatises on gymnastics and physical education, arguing for its role in creating a well-rounded citizen. The seeds were being sown for a return to structured movement, though it would be a slow germination.

The true turning point arrived in the 18th and 19th centuries with the rise of nationalism and the Industrial Revolution. In Germany, figures like Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, the "father of gymnastics," developed systems of apparatus-based exercises—including the horizontal bar, parallel bars, and vaulting horse—to promote national strength and unity among youth. His Turnverein movement spread rapidly. Simultaneously, in Sweden, Pehr Henrik Ling created a system of medical gymnastics focused on improving health through specific, measured movements with light apparatus. This was a crucial development: exercise was now being systematically analyzed and prescribed, laying the groundwork for modern kinesiology and physical therapy.

Across the Atlantic, a new phenomenon was taking root: the obsession with strength. The 19th century saw the rise of the legendary strongmen like Eugen Sandow. These performers, who headlined vaudeville shows and music halls, demonstrated incredible feats of power and displayed physiques that the public had never seen before. Sandow, in particular, became a global icon, promoting the idea that strength could be cultivated and that a muscular body was something to be achieved through dedicated training. He marketed the first widely available dumbbells, barbells, and isometric exercise equipment, effectively inventing the home fitness industry. His spectacle transformed strength from a utilitarian asset into a form of popular entertainment and personal aspiration.

The mid-20th century witnessed the democratization of strength training, moving it from the domain of strongmen and athletes into the mainstream. Jack LaLanne brought exercise into American living rooms through his television show, preaching the gospel of fitness with boundless energy. But the most significant architectural shift was the creation of the modern gym. Initially dark, gritty spaces frequented by bodybuilders, boxers, and weightlifters, they were revolutionized by the rise of commercial health clubs in the 1970s and 80s. Chains like Gold's Gym and later, 24 Hour Fitness, created accessible, social spaces filled with specialized, single-purpose machines. The Nautilus machine, invented by Arthur Jones, promised efficient and safe strength gains through "resistance training," a term that entered the common lexicon. The focus began to splinter between bodybuilding for aesthetics, weightlifting for performance, and general exercise for health.

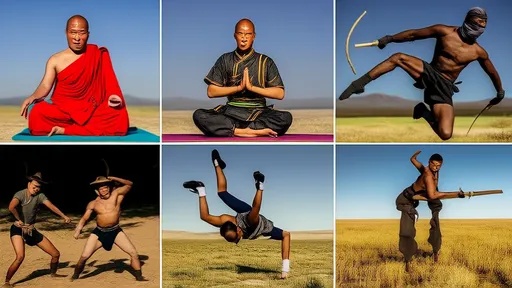

We now live in the era of the hybrid athlete and the "functional fitness" revolution. The late 20th century's isolation-based bodybuilding routines are being challenged by a return to the compound, whole-body movements of our ancient predecessors. The explosive growth of CrossFit has popularized high-intensity workouts that combine weightlifting, gymnastics, and metabolic conditioning, all performed at a community-oriented "box." Similarly, the accessibility of calisthenics or "street workout" has seen a massive resurgence, proving that the human body, with minimal equipment, remains the most versatile training tool ever devised. This modern ethos prioritizes capability—strength that is useful, mobile, and resilient—over mere appearance, echoing the functional demands of the Greek pentathlete and the Roman legionary.

Today's landscape is a synthesis of every era that came before it. A modern gym is a museum of movement history. In one corner, a powerlifter performs a heavy back squat, a movement with roots in the strongman shows of old. Nearby, someone flows through a yoga sequence, a practice with ancient Eastern origins that has been wholly integrated into Western wellness. On the turf, an athlete pushes a weighted sled, a drill straight from the training manual of a Roman centurion. And throughout the space, people are using their own bodyweight for pull-ups and push-ups, the most classical exercises of all. We have, in a sense, come full circle, blending the aesthetic ideals of Greece, the functional strength of Rome, the systematic apparatus of the Germans, the medical precision of the Swedes, and the spectacle of the strongmen into a global culture of health and performance.

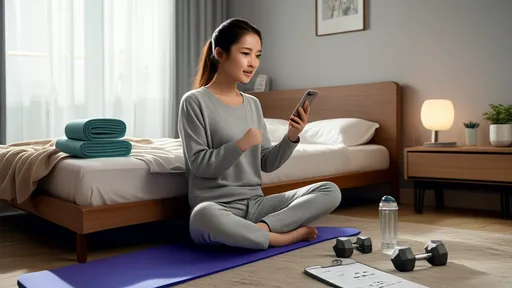

The evolution of exercise is far from over. As technology advances, we see the emergence of bio-tracking, virtual reality workouts, and AI-generated training programs. Yet, despite these high-tech innovations, the core motivation remains unchanged from that of the first athletes in the palestra: the deeply human desire to test our limits, to improve ourselves, and to experience the profound connection between a strong body and a vibrant life. The tools and the terminology may evolve, but the essence of the classic action—the push, the pull, the lift, the leap—remains our eternal inheritance.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025